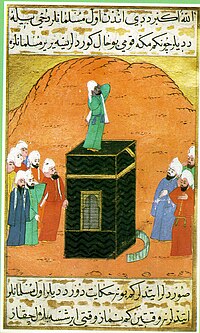

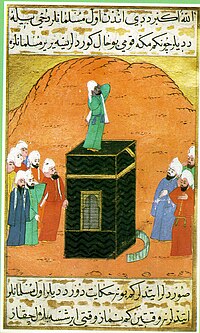

pictured:Bilal, Islam's first MuezzinA tree has fallen and those that heard it fall, weep draft

pictured:Bilal, Islam's first MuezzinA tree has fallen and those that heard it fall, weep draftby Wanda Sabir

I missed a call from my girl, Zoe, to tell me that she wouldn’t be able to attend the memorial for Imam Warith Deen Mohammed today in Chicago—Sept. 13, 2008

I haven’t written my Imam Warith Deen Mohammed reflection yet, so here it is. I was supposed to go to a concert at the Oakland Museum at 2 p.m. and here it is, 6 p.m. now 9:32 p.m. and I missed Tauheedah’s surprise birthday party, and I am almost done at 10:52 p.m. I have only moved to throw clothes from the washing machine into the dryer, take supplements, drink water and greet a friend who dropped by to say hello.I remember the first time Iman Warith Deen Mohammed visited the school—Sister Clara Muhammad School; we were at the Oakland site and the director was giving him a tour and they skipped my classroom and I didn’t get introduced. In the thirty or so years he was leader I never met him face-to-face. Funny, my daughter did and when I told her he’d died Tuesday, she didn’t know who I was speaking of.

A great man has departed the realm of the living.

I recall the news his father had passed. We were in San Francisco, the year 1974 and I’d just graduated from Muhammad University (high school) and thought I’d be able to attend Savior’s Day. Someone, I think the minister, at that time John Muhammad or Minister Majied, promised the valedictorian a roundtrip ticket. I knew I was going, so I packed my bags and waited patiently. I’d made myself a new garment top; it was a lace covered sharkskin—white, and I think I’d planned to wear my rhinestones: earrings and necklace with it. I waited and waited and no call came and then before I could get there, perhaps in the year to come, the messenger died (almost one year later to the day, I sat in my room waiting).

I knew I wasn’t going to the funeral. I don’t remember any of that. I don’t remember his last address or the one the year afterwards. No other images or words come to mind. I’m sure I was at the mosque that Savior’s Day 1975 with everyone else listening to the amplified address, seated on the sister’s side of the auditorium with my notebook. I took notes for my family. Daddy seldom attended. He was content to hear my report backs from the front. Funny, how he’d argue with me when he wasn’t there. It was just more of the patriarchal madness I ignored. It could have also been ageism.

Over the years, after the Messenger passed, some of the reports issued from headquarters, (which remained in Chicago) were hard to believe like the dietary restriction lifts. I recall Sister Elretha taking me and someone else to Fisherman’s Wharf to a restaurant to have shrimp and crab.

They’d missed shellfish and when the messenger died, the list of “cannots” did too. I wasn’t of the same thinking—I didn’t think his death meant no more fasting, eating shellfish, catfish, soy products, short skirts, marrying infidels, disregarding the Ramadan fast in December, but my beliefs were not among the more popular.

I kept doing what I’d done before and listened and watched as some people in the community without an anchor stopped coming and went back into the streets: drinking and smoking cigarettes, and participating in other behaviors no one was going to kick them out of the community over.

Gone were the gatekeepers—captains and lieutenants. There was no more FOI or MGT, Vanguards and whatever the male equivalent was called, for the male youth group. We were on our own. It was like a parent had died and now we were grown—well maybe teenagers. And if the adults were teenagers, I was a child, but an observant obedient child. I recall all the chairs coming out of the auditorium on Fillmore and Geary and red carpet installed and the first session on the floor, the men in front of the women, no longer on our side. I also recall the new flag hanging behind the rostrum. Gone was the crescent and star in the center, the initial letters for the terms: freedom, justice, equality, Islam in the four corners. The new flag still had the red background, but the center image was of an open Qur’an with golden lines radiating from its spine. Arabic script was written under the open book: La Ilaha Illah, Muhammad Rasulullah. “There is no God but God and Muhammad is His Messenger.” It’s on the masthead of the Muslim Journal, gone was Muhammad Speaks (http://muslimjournal.net/mj_home.htm).

It was a real shake-up, but I was for the ride and I held on.

We didn’t know what to expect after the Messenger died. America probably expected black people to take over. I’m sure the powers that be never expected the mild-mannered son, Wallace Dean Muhammad to lead his father’s community, now his community, on a journey which would end here Sept. 9, 2008—he began by getting out and touching people. He wanted us to know him as a flesh and blood man: he was real, had a sense of humor, made jokes, loved his wife and his kids, got sick…a regular fellow who was constantly evolving and growing each day he was allowed to see sunshine once again.

After the dust settled, Minister Farrakhan emerged as the leader of the Nation of Islam, and those of us who followed the Honorable Elijah Muhammad continued to follow his son, Wallace Dean Muhammad, who later changed his named to Warith Deen Muhammad. It meant “inheritor of the faith of Prophet Muhammad,” not his father, (but it meant that too).

He wasn’t that old—my dad’s age. They were even born the same month and year, October 1933. Everyone knew this because the Messenger’s family history was a part of the catechism we all learned –I taught my students in Muhammad University, (which Imam Warith Deen changed to Sister Clara Muhammad School after his dear mother). We learned all the messenger’s children’s names and birthdates, especially this son’s because he was the “inheritor” of the faith. We’d known he was special before his dad died. Only he was in the photo with his dad and a photo of W. Fard Muhammad on the wall over the two. Imam Warith Deen was holding a Qur’an. W.F. Muhammad is the man who taught Elijah Muhammad about Islam and proclaimed himself God. This photo was seen as proof by some that he was indeed the one to carry on the work his dad had begun back in 1930 in Detroit.

I felt at times Imam Mohammed was dismantling the community. We went from Nation of Islam with land and property to the World Community of Islam in the West and the American Muslim Mission quickly…losing our communal holdings too quickly, or so I think when I drive through the old territory where we once had thriving businesses. I don’t know why we didn’t own the property we used for our meetings and business developments.

Imam Warith Deen, scholar and teacher encouraged us to call ourselves Bilalians. Many of us toyed with calling ourselves “Bilalians” after the great muezzin or caller to prayer, Bilal Ibn Rabah. He was a black Ethiopian slave Prophet Muhammad freed when the Islamic community was the new monotheistic religion on the block—Christianity and Judaism its older siblings.

At the time the terms Negro and African American, weren’t as en vogue as black, so when WCI members checked “other” on census and other forms, a lot of us, I know I did, wrote in “Bilalian,” it didn’t hurt that my husband, at the time, had taken the same “Bilal” and that we named our first child, a girl, after him, “Bilaliyah.” This naming ceremony was an opportunity to educate others about our Islamic ancestry which we could trace beyond American captivity back to the motherland. Later on, I learned about Muslims from Africa on the slave ships that continued to practice in captivity.

I’d never heard of New Africa or New Africans, so in retrospect, I think this was Imam Mohammed’s way of showing us our special history. And then he began to write books while continuing the fourth Sunday talks nationwide.

What one noticed immediately in those early years was the decentralized governance. I think the ministers, now Imams went to Chicago to visit Imam Warith Deen for conferences, but he also travelled here. I don’t remember if the Savior’s Day-thing continued after his father passed, I just remember thinking that our new leader lacked his dad’s charisma. He was no Malcolm X or Louis Farrakhan, but if his dad felt him worthy of this enormous task, I was going to ride the train with him. He was also named after his father’s hero Wali Farrad Muhammad, alias Wallace Fard (http://www.jstor.org/pss/1385500).

What was the alternative? I didn’t want to try navigating this ship alone or even worse, disembarking. This was my life, these were my friends, this was my history; I didn’t know anything else besides this, so I stayed. Mama had left Daddy and Daddy never objected to Imam Warith Deen’s directives. He was a freethinker anyway. Outside the constraints or boxes membership leaders might want to impose, my dad always did his thing—whether it was “lawful,” Islamic lawful, NOI lawful, or not. He was the law.

So me and my little brother Fred stayed and kept going to the mosque, named changed to masjid. Everything was gradually shifted to Arabic terms. Imam Abdullah was appointed imam over the community in Oakland once Imam Warith Deen bought the property on Bancroft and 47th for the Bay Area to have a school. I remember the friction this caused, but Imam Abdullah was a lovely man and Imam Warith Deen’s teacher. From Fiji, the elder teacher, loved our imam and was almost a surrogate dad. He was a beautiful introduction to us of true Islam and its humanity. He loved Islam and the prophet, and was a gentle presence in the East Bay community. I stayed in the San Francisco mosque or masjid, where Imam Ousman Mekki was leader at that time. I think John Muhammad left when the Messenger died and started his own community.

I let Mekki deliver my wedding vows, instead of my friend, Imam Abdullah. Bad choice, but I yielded to pressure from my fiancé and father—no more than tribalism. They liked Mekki because he was black, even after they knew he was a snake. Long story.

Okay, so Imam Warith Deen Muhammad is continuing his goals of growing his community up…while connecting us with a worldwide Muslim culture. He’d been aware of the vastness of this faith, that it touched all cultures everywhere. He encouraged us to take the Qur’an from the shelves and read it. He encouraged us to take Muslim names and disregard those Xs. There were no more lessons from Chicago. When someone wanted to become a member of the community they took Shahadah or witnessed initially in the Minister or Imam’s office, later in front of the entire community.

We learned to perform ablution and began to make five daily prayers and fast according to the Islamic calendar. There were Arabic classes and Hadith classes. I never knew the difference between Sunni and Shiah for a long time—Muslims were Muslims—submitters to the will of the creator.

I didn’t know one sect didn’t acknowledge the other. Later I learned that Imam Warith Deen was Sunni and that the direction he’d led us in was the same. I found out later that his questioning of his father’s path began while in prison as a war resister. His transformation, like Malcolm’s also occurred behind bars.

I missed the cohesion of the Nation—gone were the snack shops, bakeries, restaurants, sewing factories, grocery stores, eventually schools, except the one in Oakland, youth clubs which is how I’d term “Vanguards.” I felt kind of like I was out there alone. I’d enrolled in college—UC Berkeley, and was around other people, some Muslim, others non-Muslim. I was studying Arabic and back at the ranch, so to speak, the inherent sexism in the traditional Islamic structure prevented me from sharing what I knew with the community. I’m not sure if I felt more intellectually free as a member of the Nation of Islam, but because there was a structure women shared, I felt as if the audience was larger and the brothers loved us, spoke and treated us like brothers or fathers, uncles, depending on their ages, and would protect us with their lives. All this disappeared with the second coming….Men stopped walking us to our cars, not to mention over time, speaking.

It wasn’t until years later, when men like Abdul Nassir went to Berkeley and took classes would there be Arabic classes taught, by that time I would have gotten married, dropped out of college. Even though after three years in Arabic—I was fluent, my husband didn’t want to learn from me.

Yes, we had a long way to go as a community, 30+ years ago.

With the new structure was a new set of mores. It seemed as if those who were closest to the Qur’anic literal interpretation of life were the in-crowd. I just wanted love and after the Nation dissolved so went the love, at least an expressed love—a love you could feel disappeared. I began to look outside the community for models of this…I ended up in the smaller community in San Francisco at the Muslim Center once I got divorced, and eventually joined a Sufi community for a bit. Smaller, these communities were more loving, but the separation of sexes led to feelings of dissatisfaction. I also started my ecumenical fellowship and started also attending churches with friends on occasions like the Resurrection Day.

While active in the community here, I missed all the trips to Mecca. I guess I wasn’t a part of the inner circle or group. Whatever it was, I wasn’t invited. When Imam Warith Deen was in Los Angeles speaking when I was still living at my father’s house, I had to pay for bus tickets for my brother and I, which meant I didn’t have money for board after I paid for the room. I would have been okay but I didn’t get paid that week. I think they said they ran out of money—whatever it was Fred and I ate sandwiches with meat we’d purchased and put on ice in our motel sink. Sister Elretha invited us to breakfast that weekend and we were able to vary the meal. But we felt we had to be there and hunger was not something that bothered us.

My brother and I were used to doing without. Our dad was sick and often out of work, so when the mosque ran out of money and the school didn’t pay me my teacher’s salary, or the check bounced, we didn’t eat and when we did, it was beans. We ate beans daily, plus Whiting H&G. Sometimes the diet varied between beans and sausage, beans and bread, or beans and brown rice. I think, from time to time, we had eggs. We’d put vegetables in the beans and keep a pot in the fridge. The type varied between small white and pink to pinto. For years this was our diet. It was many years after Warith Deen took over before I could trespass into dietary cannots to eat red beans, black eyed peas, and greens. In “How to Eat to Live,” these were foods prohibited I still think, for good reason. We were also told to watch our sweets and stayed away from refined sugar.

To date I haven’t made the pilgrimage to Mecca, but I have fond memories of speaking to my late God-grandmother, Sister Elretha about her trip. Now her experience is not one I’ll have whenever I go. She was the guest of a sheik and was treated like royalty.

After a while, especially after my divorce, I stopped attending the masjid in Oakland as much. I started going to the one in San Francisco, where my dad attended. By that time, his law and Islamic law were pretty much one in the same. Imam Abu Qadir Al Amin and Imam Faheem Shuaibe had reconciled, besides this, San Francisco was far enough away for each to have his own autonomy.

I stopped paying attention to personalities and focused more on the scripture and what felt right. Eventually I stopped going to the Muslim Center. After my dad died, there really wasn’t much community there for me any longer, plus all my old friends like Brother Nu’man and his wife had died.

I still can’t say I have a faith community. I still uphold the pillars of faith and fast during

Ramadan, plan to go to Mecca with my brother some time in the future, believe in the oneness of the creator and creation, and agree that all faiths are connected even when others fail to acknowledge my existence.

Imam Warith Deen established a place called New Medina in Mississippi where my friend Genevieve bought land to build a home. This is such a New African concept, I wonder if he was influenced by this. His father always told us that we were a world within a world, so my feelings of isolation, are not without substance or ground, especially with this name my father took on: Ali Batin, two of the many attributes of the creator, “the most high” and perhaps the most “hidden.”

Anyway, I am invisible to most and I have gotten used to such autonomy, loneliness, whatever.

Imam Warith Deen really put black American Muslims on the world map, just as his father put Islam on the American map—before Elijah Muhammad there was no Muslim in America movement. Ready to assimilate, the immigrate Muslim population was invisible. We were not. We would fast and dress in hijab when others claimed various reasons to justify their weakness—some still do today. I remember fasting while traveling, even though I didn’t have too.

Immigrant Muslims would signify on me as a child when I’d go into their liquor stores and purchase cigarettes for my dad, or later on as a youth when I’d go buy some candy. They’d ask me questions—quizzing me about my faith as if they were the gatekeepers. Little did I know that the majority of Muslims worldwide were not Arab, the locus certainly not in the Middle East.

This false superiority was challenged by Imam Warith Deen’s leadership and subsequent mainstreamed community. It helped his cause when doors were opened to all. Immigrant Muslims, most from Pakistan and other Sunni communities, now were a part of our community too, not to mention the white groupies who’d been denied admission before. But for the first time, their hypocrisy was challenged.

I’d been raised as a soldier in Allah’s army. It wasn’t figurative like that of the Christians. I’d learned marital arts. We had security; I was serious about the revolution and I’d learned to respect the command of those in charge. Even though the propaganda said, “White people were devils,” I knew there were black devils too, that skin color was not what made people evil, it was their hearts. White skin privilege made it easier for some to participate in the dominant paradigm which kept my people on the bottom; plus we had the added problem of low self-esteem, a residual side effect of this disease, an infection permeating all aspects of the social and economic realm—this was one of the reasons why I loved the Nation of Islam so much. It was a black nation…all my friends were black and I could meet all my needs inside the community. I didn’t have to go outside for hardly anything at all.

We had officers, lessons –there was a manual and a plan. And even when all of the external structure seemingly fell away when our leader, Dear Holy Apostle died, and his son took over, it was there, it was a part of us, which is still there and will never die.

I am a black nationalist and revolutionary sister precisely because of the Nation of Islam and what the Honorable Elijah Muhammad taught us. I was a part of what the Black Panther Party called the rank and file. I was the one who believed and followed the spirit of the word and wasn’t caught up in the dysfunction at the leadership level. The dirt touched me, but not enough to make me forget or want to erase my entire life’s history.

I believe we are all born Muslim and then society slowly robs us of our nature. I don’t believe in original sin. I do believe that evil exists, but I also believe that love is the answer to everything that ails us and should be the motivating force behind all we do.

When I’d hear certain statements by Imam Muhammad, especially around Black Nationalism and African ancestry, I was shocked initially given our history and given his father’s beliefs. But since I never had an opportunity to ask him about it I’ll just say that he never wanted us to forget our stake as a people in America, or our ancestors who lived and died for this country. To forsake this country is to forsake that history and that sacrifice. He didn’t think we should all go back to Africa and leave America forever. I don’t believe this either. I think Africa should reunite with its children in the Diaspora, and that we can then develop our global economic structure more effectively as we heal and mend the centuries old rift between us.

I say: we claim it all—Africa and America; this is the only way we’ll ever get free. Islam in this case was the vehicle, but it’s not the only vehicle.

My work has been to look at healing…we never spoke about this enough after the Messenger died and when he was alive, I don’t think it was addressed in any kind of strategic way. No, this is not true.

The messenger cleaned up our diets and bodies, helped up develop self-discipline by fasting outside of Ramadan, and cleaned up our minds with teachings of self-love and self-worth. We were also encouraged to read and inquire and grow mentally strong. He also introduced the idea that we are deaf, dumb and blind to the knowledge of self, and until we know ourselves –ancient to the future, we will continue to be slaves and servants to the enemy.

This is an aspect of black self-development, both spiritually and emotionally, the decentralized governance didn’t speak to enough, but with advisors like Dr. Na’im Akbar and others the information was there, just not implemented in any kind of way that would have had us talking about mental illness and curative measures. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad didn’t let an opportunity pass without speaking to our need to heal our bodies and our minds and our spirits.

We didn’t focus on white people and what this nation was or was not doing for us, we focused on ourselves and our community and how we could provide for our own needs.

Under Imam Mohammed we continued to embrace our sisters and brothers in the prison system, but there was no investigation into what kind of support they needed to stay free—not in 1975, but later such was established by people like Imam Qadir Al Amin and Sister Hamidah Cook, Not in Our Name.

The link between the black liberation movements was also not exploited, or explored. Sister Tarika Lewis tells me how many revolutionaries joined the Nation of Islam to escape detection. I supposed J. Edgar Hoover didn’t have us under as much scrutiny as BPP. Undercover, these warriors remain silent to this day. I just met some of these heroes and heroines in the past two years at Black Panther Party reunions.

Funny, how without a blink in consciousness I can call Imam Warith Deen Muhammad’s wife’s name, Sister Shirley. I know he had children, but by the time he was leader, the catechism had ceased and his extended family was not a topic of research the way his father’s was. I just know they exist.

Imam Warith Deen, Min. Louis Farrakhan and I think that’s it…the philosophical lineage between El Hajj Malik and his teacher the Honorable Elijah Muhammad ends with Farrakhan.

I didn’t remember to bring the book I teach: “Children of the Movement” and get his autograph the last time I saw Imam Mohammed, when my daughter was honored at the “Human Excellence Awards” program in San Francisco at Grace Cathedral. I always thought it interesting that we had to host our programs in rental facilities, that as a community 78 years after the birth of Elijah Poole, we still are not the sovereign nation he and peers and/or mentors like: the Honorable Nobel Drew Ali, Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Booker T. Washington, W.E. B. Dubois, Ida B. Wells, Madame CJ Walker, Mary Ellen Pleasant, and others, dreamed of.

We went from Mason halls to cathedrals to other convention centers. Do-for-self –collectively, kind of fell off and do-for-self as capitalists became the norm. I didn’t like the way our community was becoming less black and more immigrant philosophically. It was as if black people were encouraged to forget their blackness and African heritage and disappear into Islamic culture, so the men married Muslims from other races and cultures and so did, to a lesser degree the women. The attire looked more Arab and Middle Eastern to the point where the sisters were encouraged to wear hijab, even the facial scarf or complete coverage and with this came more sexism and physical abuse—a silent epidemic in Muslim society…this one no different.

So one day I said, no more. That day, I’d attended one of the Imam’s public lectures and this imam from Texas was insulting in his delivery. I didn’t agree with most of what he said and I decided that I was not going to attend any more masajid where women were not allowed to lead and where the women sat behind the men or were sequestered behind walls in another room.

I broke my rule a couple of times to attend Masjid Al Iman in Oakland because I like Imam Yassir Chadley, and more recently at Imam Musa’s masjid in Alameda, but when the men would not speak to me and looked through me when I spoke to them, it was like, okay, this is it—no thank you. It was Ramadan too.

My brother turned me on to the Universal Submitters and I used to attend there until he stopped going. The tendency for idol worship among human beings is such an issue. It seems if we don’t guard against it, we slip into it and this is a form of bondage and I value my freedom.

So I am going it alone and yes, I feel lonely, but since I live in a Muslim household, I can find support for the fast and see my daughter reading Qur’an and see my sister-in-law praying and if I want companionship in the daily prayers I can find it at home. I have people to talk to about scripture and can read the Arabic and can have a discussion with me. So I am blessed. I might not have a public ummat but I do have an ummat, and because I grew up in this community, I always have a home…I can always find a familiar face in the assembly.

Submission is my home. I lost touch with the daily workings of Imam Mohammed and the community. I wasn’t aware of the Mosque Cares, the signature not-for-profit entity he elected to represent his mission in the end (http://www.themosquecares.com/). What I do know is Imam Warith Deen was consistent. His goal was to raise his people, complete his father’s work and perhaps it is done. I know I certainly feel like an adult.

One of the things people told me when I made 50 this year, was that I was now grown. The tendency to blame others for one’s troubles and to give away one’s hard-earned credits for success should be over when the child is grown. Imam Warith Deen was a great parent to the community, and now another leader doesn’t need to step in….grown people lead themselves.

I’ve gotten emails and copies of posts in the on-line funeral guest book. Men are offering themselves as the new leader for this nation. I guess along the way they stopped listening ‘cause the Imam was clearly not about idol worship and though his followers wanted to canonize him, he resisted such to the end.

I hadn’t known, until reading an article about the funeral Sept. 11, where 8000 people were counted in attendance that he rebuked his father’s leadership several times and was not allowed to come home. His daughter said he reconciled with his father (the last time) just six months before the leader of the Nation of Islam died February 25, 1975. I forgot the differing points of view between Imam Warith Deen and Min. Farrakhan, the rivalry between the two and the split until the breach was healed in 1999. This split was not something fostered by members of our community, as I recall and Imam Mohammed said as much to Farrakhan. I always looked to members of the NOI as my Muslim brothers and sisters. I saw them in the early stages of evolution…and if the NOI structure was useful then more power to them.

I think my participation in the World Community of Islam in the West and American Muslim Mission, must have stopped around the time the name of the community shifted to the American Society of Muslims. It was hard to find Muslims who were about the work I was interested in, the uplift of black people and healing our community, whether that was looking at HIV/AIDS, domestic violence, women’s rights or African American self-determination. In his embrace of what we used to term “true Islam,” it often seems as though Imam Warith Deen threw out the baby with the bathwater. I see now such was not necessarily the case.

What he did was revolutionary, but he was not a black nationalist. His work was revolution of the black spirit and the vehicle he chose was one that worked for him, Islam, not that this was the only vehicle.

For him to have departed this life, the ninth day of Ramadan and to be interned on a day associated with evil, the prime target people who claim the same faith he did, was an opportunity, many cited in Chicago Tribune articles I read, to change the day of national mourning into a national celebration of the life of a man devoted to service.

I can’t think of a man who loved his people more than Imam Warith Deen Mohammed did, no matter how frustrating or personally tiring or taxing to the spirit this was. His story is not the story one hears when heroes like Martin King and El Hajj Malik is told, because he lived—and to live while society’s heroes are saluted only once they are deceased is hard too.

He lived as his big brothers, Malcolm and Martin, were cut down. I wonder if this is the reason why outside of Chicago much more noise hasn’t been made by the nation at the transition of this man. It is the same noise I expected when Ray Charles died and was buried, his memorial eclipsed by that of a criminal, Ronald Regan (I think…or some other dead president).

President Bush should have made a statement; Imam Mohammed’s death should have been in the national news, throughout the week. Even now, outside of the mentions in the Oakland Tribune and other local papers past one-day coverage 9/10, I have to do an Internet search.

Perhaps he lived too long—a 74 year old black man less than a month from his 75 birthday?! I say, more cause for celebration, but I’m not on those editorial boards. We should call and complain at CNN.com and other network stations.

It is way past time that he was cover story on one of the major news magazines—even now, the opportunity hasn’t passed. The stories written about Black Muslims as if we were some kind of plague on the nation (America) were somewhat appeased when the Honorable Elijah Muhammad died and his more mild-mannered successor took the reigns of this organization.

We weren’t Muslims; the propaganda separated us and made us: black Muslims as if there was a difference. To date, a Muslim in America who is black is a black Muslim and presumed one who converted to Islam and is not as authentic a model as an Arab-Muslim-model is, when such couldn’t be further from the truth. This is the reason why I think Don Cheadle’s latest film, “Traitor” is so good. In the film he is a Muslim raised in Sudan, moves to the United States, fights in the army, and then finds himself trying to correct a wrong. He reframes the image of Muslim and how a person’s faith can manipulated by others who don’t value life. Sameer values life and weeps when life is lost, even in war. (Watch an interview at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xDkVjMQXkbk and http://www.scrippsnews.com/node/35770)

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad called us a nation and this country a beast about to be destroyed, a country we wanted no part of. His son disagreed. Imam Mohammed participated in American society becoming the first Muslim to deliver an invocation to the US Senate (1992) and in 1993 and 1997 he was the first Muslim to recite Qur’an at presidential inaugural interfaith prayer services (Chicago Tribune).

Imam Mohammed made Islam more palatable to mainstream America and made it easier for immigrant Muslims to realize the American dream, a dream still elusive to most African Americans, Muslim and otherwise.

Just as Martin King, a little older than Imam Warith Deen, more his late brother Herbert Muhammad, former manager for Muhammad Ali’s peer, Imam Warith Deen Mohammed, laid the ground for religious tolerance in America between Christians and Jews—we all believe as Muslims that we’re all “people of the book,” and share a common prophetic lineage. In steering his father’s community into Orthodox Islam, he pacified the detractors and their henchmen who were out to discredit our integrity, those who said Islam was a front for terrorism.

Not here, it wasn’t.

Remember, the Nation of Islam was established before WW2, just after the Depression. This predates the Jewish partitioning of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Movement. It predates the pronounced immigrant population throughout America today, where there are enclaves of South Asian Muslims and East Asian Muslims with mosques and schools. There is a Little Kabul in Fremont, California, and in Detroit where Temple No. 1 was established in the ‘30s there is a huge immigrant Muslim community today.

When the Honorable Elijah Muhammad (October 7, 1897-February 25, 1975) accepted Islam and he and his wife Sister Clara Muhammad began to build a nation, Islam was not the fastest growing religion in the world and America was not familiar with the religion or people who followed Prophet Mohammed, (PBUH), let along the Messenger of Allah, a black man from Sandersville, Georgia, the child of sharecroppers, hailing distance of the plantations which so many other blacks in America had escaped from during the great migrations north and west.

Elijah Poole, one of 13 children to Willie Poole, Sr. (1868–1942) and Mariah Hall (1873–1958), was added to the watch for a black messiah when he came out as leader of this new movement. The NOI’s ability to realize its full potential was compromised by the human tendency to deceit, both of one’s self and of each other, fed in this case by the tendency of most black people to distrust other black people, especially those in leadership positions.

Though Elijah Poole had a third grade education, and was the son of a minister, he wanted to excel and do better than his parents, just as his son, Warith Deen, wanted to do the same. Warith Deen graduated from high school and went to college. Throughout his life he studied his religion so that he could serve his creator and his community to the fullest of his ability and encouraged all of us to do the same.

His father, Elijah Muhammad’s story is remarkable and despite his mistakes, I think the good certainly outweighs any wrongs his leadership and human frailties might have caused to taint this remarkable record as founder of a great example of black autonomy and leadership—from the belly of the beast we were able to do great things, and despite the dissolution of this legacy due for the most part of graft, the fact remains, we did it. I liken the mistakes to the mistakes New African nations are making to date, mistakes many of us have expertise we could share to help prevent or stymie its continuance, but how many folks who know allowed access to people in power who need to know.

I hadn’t known that Imam Warith Deen Muhammad also spent time behind bars as a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam and that his objection to his dad’s leadership during the ‘60s and ‘70s was continuous as was his expulsion from the community again and again for his principled disagreements with dad—he and Malcolm agreed, yet unlike Malcolm, Warith Deen was publically forgiven. (His father was also jailed for draft evasion, even though at the time, he was too old to serve (1942).

The Imam was truly amazing and the breath of the work and evidence of his love for his people is not truly known, nor its loss really felt, but despite the absence of news and the fact that the planet hasn’t stopped rotating–a tree has certainly fallen and a pause for this great man’s life is due, now and forever after.

His was a life given to service and I thought when I heard he’d passed, that perhaps his work was done. Similar to the work of playwright August Wilson, who died as soon as his final play of the ten-work series had had its debut, just before his 60th birthday.

He was a quiet man who life was like a dew drop on a leaf—its silent impact immeasurable. When he was around, one sensed his deep commitment to his work. Kindness beamed from his expressive eyes and though famous one never felt any airs or visions of grandeur. He was approachable and attentive. I was just shy and never crossed the threshold into his line of view other than a nod his way. I hope the journey home is swift and his reward all he one could hope for.

I also pray Allah ease the hearts of his loved ones left behind, his wife, children, grandchildren, siblings, other relatives and friends.

Visit http://newafricaradio.com/ You can listen to archived lectures, and purchase recent books.