Placas: The Most Dangerous Tattoo by Paul S. Flores at LHT Sept. 6-16, 2012

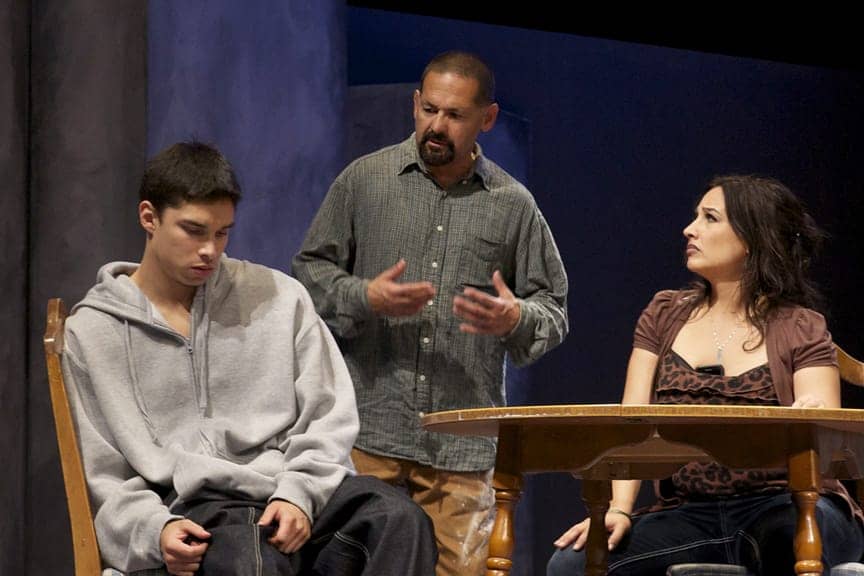

Paul S. Flores’s new play Placas: The Most Dangerous Tatoo, starring Ric Salinas of Culture Clash, as “Fausto Carbajal,” Cristina Frias as “Claudia Villalobos,” Ricky Saenz as “Edgar Carbajal,” Luis “Xago” Juárez as “Largo, Scooby,” Sarita Ocón as Liz, Bugsy, Mama Nieves,” Juan C. Parada as “Orozco, Nelson Carbajal, CARECEN Technician,” and Eduardo DeColosio as CARECEN Technician, Homeboy, directed by Michael John Garcés, currently on stage at the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre, 450 Post Street, San Francisco, is riveting. I was sitting on the edge of my seat all through intermission, the drama was that intense and unsettling—Fausto, Edgar’s father, spends nine years in prison and upon release decides to have his tattoos removed for his son, whom he doesn’t want to follow in his footsteps.

What a journey Flores paints for us here with this play, illustrated with such a fine cast. Each actor one of the many colors in a palate which is vivid in its imagery and language—so appropriately named, Placas, barrio slang, a code word, Flores says, for graffiti tags, a nickname for body tattoos, yet, Flores's "Placas" is more than body ornamentation, placas hide and disguise as they camouflage true intent and meaning. They are often impenetrable barriers and armor youth wear to hide pain and disappointment.

No one goes into hiding willingly, so what precipitates this retreat and what are some of the consequences of the choices made here? Luis J. Rodriguez, Chicano writer and poet, speaks of this trade off often as "la vida loca" or the crazy life in his memoir: Always Running: Gang Days in LA. The big cover up is not the act of sanity rather insanity. . . a slow descent into hell, one of annihilation or erasure, one of oblivion.

Fausto's tattoos are so numerous and their stories so powerful, he becomes trapped in a narrative he has outgrown, yet cannot escape as long as these words and symbols often signifying death, occupy his body via its largest and most visible organ--his skin. Sekou Sundiata, late poet, has a poem about about skin and the judgements attached to skin pigment. He says the perceptions and regard one receive "all depend on the skin you're living in" --imagine if this skin is placas enhanced?

It's complicated.

Flores's character Faustos is disdained and harassed by a rouge Salvadorian American policeman, "Orozco" while a few blocks away he is given a pass by homeboys who recognize him and give him respect. Fausto, like his name implies is also "lucky," but eventually even Fausto's nine lives run out.

Flores’s play is written in two languages: Spanish and English, the juxtaposition purposeful as one misses the humor depending on one’s linguistic elasticity. Yes, Placas in the hands of veteran actor, Ricardo Salinas, born in El Salvador and raised on the streets his character walks bring with it an authenticity to the role few could match—an authenticity and Culture Clash humor.

Gone all of his son’s formative years, Fausto's son Edgar is raised by his teenage mother--party girl, more in the streets than at home, and all the wrong friends, friends who are members of a rival cliqa or gang than his incarcerated dad.

This play takes place between the clinic where the father has his tattoos burned off with lasers—the apartment where the young man, his mother and sister live, the grandmother’s house where the parolee dad stays, visited often by his born again Christian brother and the streets which makes heroes out of villains and orphans out of fools or the foolish.

Stark. Placas's set design is a brutal desert where the only art is on the bodies of its characters. Yet this art is not culturally liberating, rather stifles as it strangles.

There is a little Stanley "Tookie" Williams, Crips co-founder, here, when one hears how the cliqa was formed. Placas is Fausto’s redemption song. Williams doesn’t get the opportunity to save both his sons, however, his writing from behind bars saves many more sons caught in the trap placas or gang armament represent.

The glossary included in the program is cute perhaps in retrospect but what can one do with it while the words are spinning their ethereal magic (smile)?

El Savador is one of the places where the Garifuna people live, the Africans relocated by the Spanish in an attempt to alienate black community. However, just as the indigenous Salvadorians resist colonial invasion to date, so do Garifuna people with the work of culture workers like the late Andy Palacio continue to lift up their presence through music which carries with it a language which was disappearing along with its people. The importance of language to story to heritage is another aspect of Flores’s play. The fact that I do not understand much of the dialogue until the character translate parts of it just means I need to increase my linguistic acuity (smile). It also means that perhaps I am not the intended audience.

I am reminded of Bigger Thomas in Richard Wright’s Native Son. Thomas just wanted to fly airplanes and even that dream was too big for a black boy who was so nervous when he was given respect and treated like a human being, he freaked and killed the girl who befriended him and the girl he feared.

Like Bigger the kid, “Edgar,” had his team all mixed up—he thought the streets were where his friends lived, when actually, his ally was his estranged dad, “Fausto,” who returned to save him, a father who loved his son.

We never get the complete back story, but there is something about El Salvador and rebels and amnesty and running and fear and who knows whether the fear was here or there, imagined or real that complicates an already complex situation— the boy’s uncle is dead, indigenous Salvadorians killed from 1522 to now and so many others. Yet, Edgar knows nothing of his parents’ histories, mother nor father.

There is an urgency involved in every transaction. It is as if Fausto in living on borrowed time. . . . At one point he stands on the corner where he is shot and left for dead many lifetimes ago and questions his rise from those ashes.

Placas is the story of mad and angry youth who have dreams of being firemen but are afraid of heights. It is the story of children like Peter Pan who wander alone in the woods so long, Disneyland seems like home even when the electricity goes out and the Fat Lady is the only one singing out of tune. These children wake up shivering cold without any comfort—they jump each other into gangs as if pain is love.

No one is immune from gangs and gang life, rich and poor, educated and illiterate, high school dropouts and college graduates. What I love about the characters is the tenderness that lives under the placas—Edgar’s rush to comfort his baby sister, the way he holds her and rocks her in his arms . . . the courage his father demonstrates when he has his placas removed and then walks into enemy territory to save his son and family—ex-wife and her child with another man. Then there is the boy’s mother, Claudia, and her story, once called “Sparky”—Mom’s tattoos and what they mean, from the one of her dad behind bars to the one on her arm she had changed weigh heavily on her as well. It is as if both mom and dad wonder, when they look at Edgar, what they could have done better, but then they were children when they had him, at least at 17, Claudia was.

The father and his brother started the cliqa because they didn’t fit in and they were being picked on. It was the same with the boy’s mother—Mexican, but denied access because her skin was a bit darker, her build different. And then their son, a good boy, who thinks he owes something to the streets and the people who live there.

Placas is not a happy story, but certainly it is one which is real, as in today and classic in its themes of family and community and a coming of age in San Francisco’s Mission District at a time when public education is failing many children—children who are stuck in Special Education and then kicked out of school, funneled into juvenile prisons and then graduated into adult penitentiaries. For information about tickets visit: sfiaf.org or call 1-800-838-3006. Tickets are $15-40. Seniors and full time students $2 off. Groups of 10+ $5 off per ticket. Call (415) 399-9554 for details.

Placas is having a series of events connected to its run Thursday-Sunday, Sept. 6-16, 8 PM evenings and Sundays at 3 PM. Saturday, Sept. 8 & 15 at 6:30 PM there will be free pre-performance discussions. This Saturday there will be a discussion: Peacemaking: A report on the Gang Truce in El Salvador, panelists include Luis J. Rodriguez and Alex Sanchez.

Sat., Sept. 15: Youth Healing from Violence: A Community Conversation

Post-Performance Events:

Sat., Sept. 8: Reception with the artists following the performance

Thursday, Sept. 13: An Evening Honoring Mission Cultural Center’s 35th Anniversary

Listen to the interview on http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks/2012/09/07/wandas-picks-radio-show Paul is the last guest.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home